hen Olympic Junior College opened for registration Sept. 4, 1946, World War II veteran Bob Ness was one of the first people to sign up for classes.

hen Olympic Junior College opened for registration Sept. 4, 1946, World War II veteran Bob Ness was one of the first people to sign up for classes.

“I was there because I wanted to get somewhere and Olympic opened the door,” he recalled.

Ness, whose full name is Charles Robert, had finished South Kitsap High School early and enlisted in the Coast Guard, eager to take part in the war effort and see the world. By the time he returned to his parents’ farm near Port Orchard in the summer of 1946, he’d done both, traveling to Italy, the Philippines and New Guinea as part of a troop-transport operation supporting the planned invasion of Japan.

The 19-year-old’s worldview and ambitions had broadened, but his opportunities at home had not. “I had visions of an apprenticeship in the machine shop at the shipyard, but after the war, they were laying people off and there were no opportunities. For me, Olympic College answered everything. Mother and father were very relieved.”

Now 89, Ness recently talked about how enrolling in the then-junior college set him on the path to a successful career as a water resource planner. The agricultural engineer helped design some of the federal government’s first Columbia Basin irrigation projects, which turned more than 670,000 acres of desert into productive farmland.

“Without Olympic, I don’t know what I would have done. Maybe I would have got an odd job on a dairy farm somewhere. Maybe I wouldn’t have gotten very far. I don’t know. “

“OC opened my eyes up to what the possibilities were and I am forever grateful for that.”

When Ness came home from the war, he had earned three years of G.I. benefits, but didn’t have the resources to go away to a four-year university. Olympic Junior College offered an affordable option close to home with tuition at $35 a quarter. Ness paid for his first year of pre-engineering studies with his benefits and worked evenings as a janitor at South Kitsap High School to pay for the second.

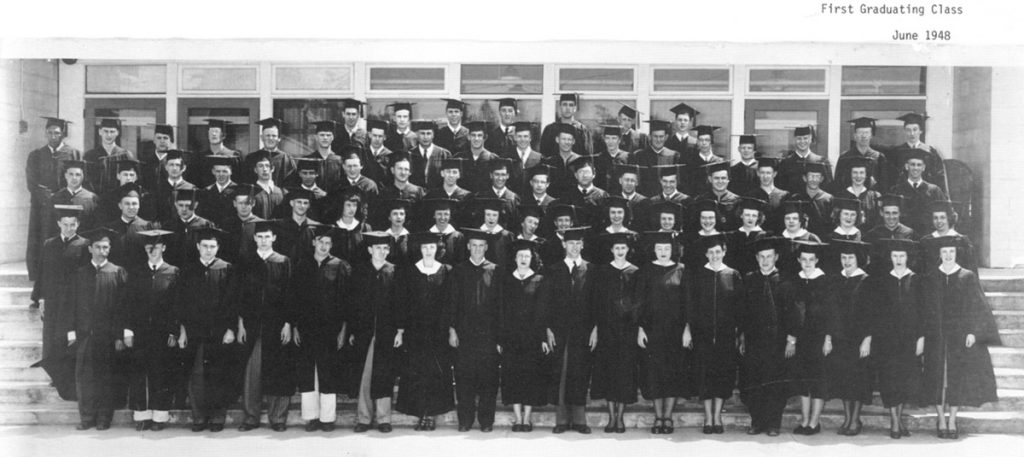

After earning an associate’s degree as part of Olympic’s first graduating class in 1948, Ness transferred to Washington State University, where he used the remainder of his benefits to obtain an engineering degree.

According to “Time After Time,” a history of Olympic College published in 1996, Ness was in good company. Some 225 of the college’s 575 full-time students in the fall of 1946 were using the G.I. Bill to help pay tuition and living expenses.

The push for a community college began in Bremerton around 1935, but had been put on hold during World War II. It was restarted in 1945, in part, because of the flood of returning veterans needing job training and the promise of funding from the GI Bill’s education benefits.

“This venture into extended pre-professional and vocational training by this community was a most timely move,” Dean Donald S. Patterson wrote in the first Olympic Junior College yearbook.

Originally part of the Bremerton School District, the college facilities included a former elementary school building, repurposed wartime dormitories and science labs shared with the high school. There were 19 faculty members. Staff included a veterans’ advisor and four veterans’ training officers.

Ness, whose photo in the 1947 annual shows a fresh-faced young man with slicked-back wavy light brown hair and a friendly half-smile, said his junior college teachers were outstanding. Some were retired from other jobs, he recalled, and they brought real-world knowledge to their work, as well as a passion for helping their students.

A particular favorite was Dr. Alfred Seckel, a mathematics professor who had fled Nazi Germany with his two sons. “I got to know him and he helped me several times.”

Ness liked the practical focus of all of his classes. “If you learned mathematics, you learned how to apply it a little bit,” he said. “It was skill-teaching instead of diploma-type teaching. All the teachers did that, Dr. Seckel, particularly.”

Ness said it was a smooth transition to WSU and then to his first job in Ephrata, where he designed farm irrigation systems. Eventually, he oversaw water resource planning for 10 western states from the Department of Agriculture’s regional office in Portland, before retiring in 1982 and moving home to his parent’s farm with his wife, Sally. The couple is active in the Sons of Norway Oslo Lodge in Bremerton, which has supported Olympic College with two endowed scholarships.

“Olympic College gave quite an opportunity to Bremerton,” he said. “There’s a benefit I see in having a college that is responsive to local needs and support. They do it together, local industry and the college.”

Ness also noted that the college continues to prioritize educating veterans – the second highest number among state community colleges, according to a 2014 report. To support that mission, Olympic College recently won a $300,000 grant to create a Center of Excellence for Veteran Student Success that’s designed to monitor student success and provide support if students are struggling.

Ness hopes other veterans get the same boost from the community college that he did: “OC opened my eyes up to what the possibilities were and I am forever grateful for that.”